We'd love to have you access this content. It's in our members-only area, but you're in luck: becoming a member is easy and it's free.

Already a Member?

Not a Member Yet?

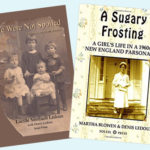

Shouldn’t writing another person’s memoir be called writing biography rather than writing memoir? You the writer are, after all, not the subject. Doesn’t that make it a biography? But, are there occasions when a biography can justly be called a memoir? In one of my books, A Sugary Frosting / Life in a 1960s Parsonage, […]

Shouldn’t writing another person’s memoir be called writing biography rather than writing memoir? You the writer are, after all, not the subject. Doesn’t that make it a biography?

But, are there occasions when a biography can justly be called a memoir?

In one of my books, A Sugary Frosting / Life in a 1960s Parsonage, I used lifestories that my late wife Martha Blowen had composed—and to which I added text. And…

I called the finished book a memoir.

Was this appropriate?

How did I presume to call it a memoir and not a biography?

When you are both a story teller and a story keeper, and being in relationship with someone who is verbal— very verbal, for thirty-one years, you get to know many of her stories.

A number of them you know not only because they were told directly to you as you went about your day—perhaps driving together into town or as you began your morning facing the woodstove sipping your coffee—but also because she told them to others in your presence.

Often, when this happens, details are added in the retelling or an emphasis changed for the benefit of the new audience—and, unexpectedly, you understand an angle to the story that had eluded you earlier.

Martha wrote a number of her stories, always in segments. She intended to write a memoir, but her life was cut short by breast cancer before she could realize this goal.

Wanting to compile her memoir, I collected her compositions into a manuscript and soon realized details were missing, details that I knew not only to be true to her storyline from my experience but that I understood to be also necessary to bring out the meaning of her story.

Soon enough, I was in a situation where I had to write another persnon’s memoir if it was even to be recorded. I found myself adding her words that lived within me into the narrative. These words of hers contributed not only scenes and conversations, but also whole stories. Eventually, more of the stories written in the first person originated in the stories I had heard from her than from her own composition.

What to do? Was it all right for me to write so extensively in the first person?

Because I have been a ghostwriter for many years, entering into someone’s sensibility is a facility that I have long practiced. A good ghostwriter is always writing in the subject’s voice—in the first person. A ghostwriter uses the vocabulary of the subject and enters into the sensibility of the person whose story is being preserved.

When I wrote my mother’s memoir, We Were Not Spoiled, I used stories my mother had told me, and I used stories from memory—stories I had been part of or stories my mother may have shared at another time.

But, this was decidedly different as I read everything back to my mother and she responded to the text.

In the case of A Sugary Frosting, and My Eye Fell Into The Soup, the story of her first year with cancer, Martha was not available to read back to.

Writing another person’s memoir

Writing in the voice of the subject has always been an energizing challenge of ghostwriting. In writing A Sugary Frosting, when I found myself writing something that fit the drama of Martha’s story as I understood it, but about which I was not certain, I would feel a tug toward what felt like “The Story,” toward something that demanded to be told. When I felt this pull, I sensed that I was being directed towards the factual, towards the authentic.

There were other times, fortunately for the truth of the story, when I felt uncomfortable. Perhaps I was imposing my “take” on her story? I usually decided to leave this material out.

The bulk of the text in A Sugary Frosting presented as Martha’s memoir has been ghostwritten. From what many readers have told me, it is impossible to pinpoint where the stories she wrote end and where the ones I ghosted begin. That is as it should be. A ghostwriter must be invisible—or why call us ghostwriters?

But is it okay? Where do I presume the authority to write another person’s memoir?

For starters, I promised Martha that I would write her stories—for our grandchildren who were not yet born—and for readers. This gave me a sense of writing in her stead—and it bestowed a certain authority.

She had also said, “I trust you not to write anything that would embarrass me.” I have endeavored to use that request as a guide—and that too has given me a sense of authority to write her story.

I believe Martha would have approved of A Sugary Frosting and would easily have called it her memoir. But…

For those readers who are still unsettled, I am perfectly comfortable with your calling this a “fictionalized memoir” or a “memoir fiction”—but what I believe it to be is a “co-authored memoir.”

Writing My Eye Fell Into The Soup

After Martha’s death, I very much wanted to write an account of her illness. I knew to do that, to really do credit to the etiology of her illness, I had to go earlier in her life. I felt that her cancer–cancer was called the disease of hopelessness in the 19th century–had roots in her early family life. The influence of these years perdured into the present.

(In Writing More Deeply, I explore the relationship between pain and truth. It’s worth a view.)

Because of this belief of early childhood influence, I wrote A Sugary Frosting. Then, having written that book, I wanted to write about the time of her illness—which was my real goal. This task was actually easier as I had her voluminous journals to quote. When I combined them to mine, I had a text.

Even in My Eye Fell Into The Soup, I had to create some text if publishing another person’s memoir was going to succeed. Sometimes, it was to explain an element and other times it was to create a transition from one entry to another, a transition that she had not made in her journals but which was necessary for the reader.

In conclusion

I have one more volume to write of Martha’s illness, and then I will be through with writing biography as memoir. I have no intention of ever writing a straight biography.

And you? What are your thoughts? Please leave a comment.

Here’s a link to our video COMMITMENT vs INTEREST. I succeeded at writing A Sugary Frosting and My Eye Fell Into The Soup because I was not only interested in writing these books: I was committed to doing so.

Remember: “inch by inch, it’s a cinch; yard by yard it’s hard.”

Good luck writing your stories—or, writing another person’s memoir!

PS: To view the YouTube video which expands on this post, click here.

No comments yet.